The mighty miniature of the Wet Tropics – Meet the Mountain Thornbill

- Ceri Pearce

- Oct 7, 2025

- 6 min read

Ceri Pearce | Birds with Altitude Project Leader

If ever a bird proves great things come in small packages, it’s the Mountain Thornbill (Acanthiza katherina). Endemic to Queensland’s Wet Tropics, this little bundle of feathers tips the scales at just 5-8 grams – about the same as one or two teaspoons of sugar – and measures only 10–10.5 cm from bill to tail.

They may look like “little brown jobs” at first glance, but take a closer look and you’ll find one of the region’s most distinctive and imperilled residents. This energetic species is endemic to a very narrow slice of upland rainforest, and its populations are now declining due to climate change.

Identification at a glance

Males and females look alike. Their upperparts are pale grey-olive to olive-brown, paler underneath, with buffy-yellow flanks that become more yellowish near the vent. A creamy-white iris stands out against the face, while cream scalloping on the forehead and a pale throat with faint streaking add to their subtle beauty. The warm brown upper tail coverts finish in a blackish band near the tip. Bills are thin and straight with a slight hook at the end, mostly black, and just 10-13 mm long. Legs are dark grey to black with a dull pinkish tinge on the tarsi and toes. Juveniles sport a yellow gape, duller plumage and darker eyes (Gregory & Matsui, 2018; Menkhorst et al., 2019; BirdLife Australia, 2023; Freeland, 2024).

Observe the creamy-white iris, cream-scalloped forehead, pale, faintly streaked throat, buff-yellow flanks, warm-brown upper tail coverts and dark legs and bill.

Confusing lookalikes

Mountain Thornbills may be mistaken for Brown Gerygones (Gerygone mouki mouki), which share similar habitat. However, the Thornbill has a pale iris (versus red in the Gerygone) and dull yellowish underparts (versus whitish-grey). Brown Gerygones also show a more defined pale supercilium and dark eye-line, and have whitish spots on the tail tip. Mountain Thornbills can also be confused with the Atherton Scrubwren (Sericornis keri) and Large-billed Scrubwren (Sericornis magnirostra), both slightly larger, darker and browner overall, with dark red eyes and pink legs (Gregory & Matsui, 2018; Menkhorst et al., 2019).

Voice

Although its calls are highly variable – from twittering contact notes to complex melodious songs with rapid sliding whistles and occasional harsh notes – much remains unknown. Do males and female calls differ? Do young birds beg vocally? Is mimicry used, as in Brown Thornbills? (BirdLife Australia, 2023; Freeland, 2024).

Where they live

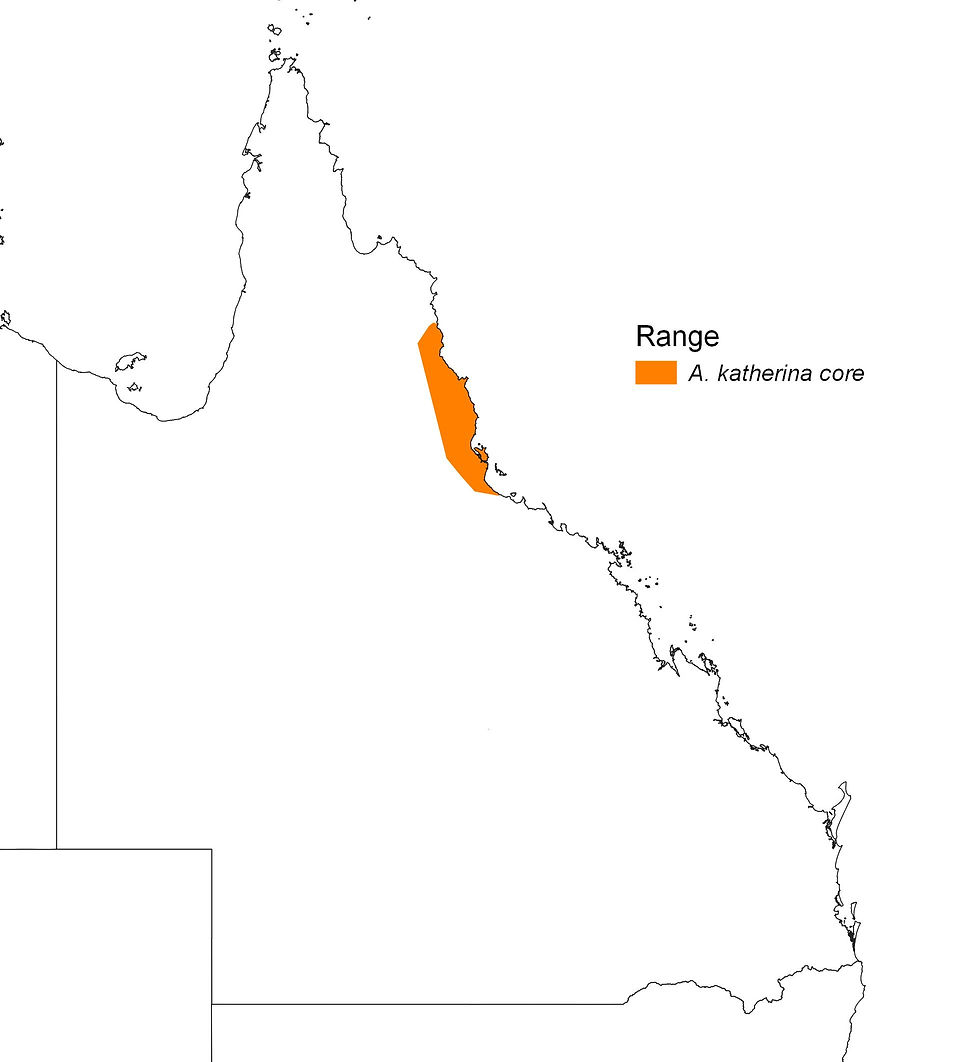

The Mountain Thornbill is restricted to eastern upland vine forests between Cooktown and Townsville (Gregory & Matsui, 2018; Menkhorst et al., 2019), typically from 450–1600 m elevation in mesophyll to notophyll (and locally microphyll) rainforest. Recent records indicate a contraction to higher, cooler, forested areas (BirdLife Australia, 2023; Freeland, 2024).

A review of Mountain Thornbill records in BirdLife Australia’s Birdata from the past five years showed detections at Julatten and Mount Lewis, Mount Hypipamee National Park, Tully Falls Road near Ravenshoe, Crater Lakes and Curtain Fig National Parks, the broader Mount Evelynn and Malanda areas, and Mount Baldy. The species was also detected at other upland sites across its range, though these records were less frequent (Birdlife Australia, 2025).

Figure 1. Mountain Thornbill distribution map. Source © HANZAB BirdLife

Busy little foragers

Mountain Thornbills rarely pause for long. They forage in pairs or small flocks, gleaning small invertebrates from leaves and branches in the mid to upper canopy, occasionally chasing flying insects. They are seldom seen on the ground.

Breeding – a rainforest challenge

Breeding commences with the onset of the wet season (as early as August through January), when insects are abundant.

Their nest is a feat of messy engineering: an irregular domed structure 12–20 cm long and 8-12.5 cm wide, with a hooded side entrance about 4 cm across to keep out rain, and sometimes a little “beard” of material hanging beneath the nest. Using grass strands, vine stems, fern fronds and/or palm leaflets, both parents construct the nest around and incorporating twigs or stems of the nest tree, then, the outside is liberally decorated with moss for camouflage and waterproofing; the inside lined with fine plant fibres and feathers (BirdLife Australia, 2023; Freeland, 2024).

One to three eggs are laid, with incubation estimated at 16–20 days (based on other thornbill species). Chicks are altricial – blind, featherless and fully dependent. Fledging probably occurs at 14–16 days, but data are lacking (BirdLife Australia, 2023; Freeland, 2024).

There is a report of cooperative breeding at Mount Lewis, where four birds helped feed chicks – likely both parents plus two helpers. As in other thornbill species, helpers may be non-breeding adults or delayed-dispersal offspring (Freeland, 2024).

The Shining Bronze Cuckoo (Chalcites lucidus) and Sahul Brush Cuckoo (Cacomantis variolosus) parasitise breeding Mountain Thornbills (Freeland, 2024).

Despite their size, banding records show Mountain Thornbills can live nearly 15 years (Freeland, 2024) – remarkable longevity for a bird so small!

What we still don’t know

Despite being a distinctive Wet Tropics endemic, the Mountain Thornbill remains poorly studied. Key aspects of its ecology – including chick development, fledging times, juvenile dispersal patterns, group social organisation and behaviour, survival rates, the frequency of cooperative breeding and detailed call repertoires and their use – are based on very limited observations or are inferred from related species. Even its distribution at lower elevations is unclear due to recent range shifts. Filling these gaps is essential for understanding how the species may respond to climate change, and for planning effective conservation measures (BirdLife Australia, 2023; Freeland, 2024).

Conservation Status

Vulnerable

According to IUCN Red List criteria (Garnett & Baker 2021), the Mountain Thornbill has a conservation status of ‘Vulnerable’, with population declines of 30-50% over the past decade and further declines predicted. Climate change – particularly heatwaves causing direct mortality and prolonged droughts reducing insect prey – is the primary threat (Williams & de la Fuente 2021). Despite this, both the Queensland and Commonwealth Governments have not revised the conservation status of Mountain Thornbill, where it is still listed as ‘Least Concern’ (BirdLife Australia, 2023; Queensland Government 2024 and 2025).

A call to action

Citizen science matters

Research monitoring of Wet Tropics birds ceased in 2016, just as declines in at least 14 endemic species were identified. We urgently need new and ongoing data.

BirdLife Northern Queensland’s “Birds with Altitude” Project invites citizen scientists to help. By surveying birds in five Key Biodiversity Areas of the Wet Tropics region and entering observations in Birdata, you can directly contribute to understanding the distribution and population dynamics of this species, which can help us in conserving this vulnerable miniature rainforest bird.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Drs Cliff Frith and Peter Valentine for their critical review and provision of constructive editorial guidance.

References

BirdLife Australia (2023). Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic Birds. Volume 1 to 7. BirdLife Australia. https://hanzab.birdlife.org.au/ Accessed September 19, 2025.

BirdLife Australia (2025). Birdata. https://birdata.birdlife.org.au/

Freeland MBH (2024). Mountain Thornbill (Acanthiza katherina), version 2.0. In Birds of the World (SM Billerman, Ed.). Cornell Lab of Ornithology. https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/home Accessed September 19, 2025.

Garnett ST & Baker GB (2021). The Action Plan for Australian Birds 2020. CSIRO Publishing.

Gregory P & Matsui J (2018). Field Guide to Birds of North Queensland. Reed New Holland Publishers.

Menkhorst P. et al (2019). The Australian Bird Guide (revised edition). CSIRO Publishing.

Queensland Government (2024). Nature Conservation Act 1992. https://www.legislation.qld.gov.au/view/html/inforce/current/act-1992-020 Accessed September 19, 2025.

Queensland Government (2025). Threatened species conservation classes, Queensland. https://www.qld.gov.au/environment/plants-animals/conservation/threatened-species/classes/conservation-classes Accessed September 19, 2025.

Williams SE & de la Fuente A (2021). Long-term changes in rainforest bird populations: a climate-driven biodiversity emergency. PLOS ONE 16(12): e0254307.